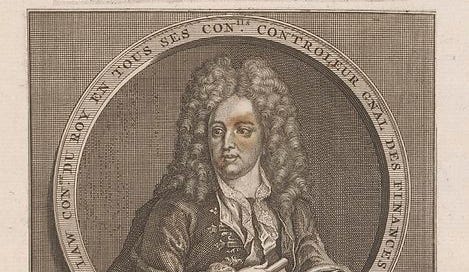

John Law’s bubble stock collides with the plague

The life of John Law (1671–1729) is a rags-to-riches-to-rags story that is nearly beyond belief. Just as phantasmagorical was the backdrop of speculative and pandemic miasma woven into Law’s adventures.

Just into his 20s, Law was bankrupt and imprisoned in a London jail, sentenced to death for killing a man in a duel over a woman. From these depths he became the richest person in Europe, outside of royalty.

Just days before going to the gallows, friends helped Law escape and flee to Europe. On the continent, there were not many job opportunities for him. He had apprenticed in his teens to be a banker in Edinburgh but didn’t have any letters of introduction or recommendation to deliver to prospective employers.

That left the gambling tables in the salons. Law took his gambling seriously, studying treatises on probability and mastering methods for calculating odds during card play. By his mid-thirties, he had a net worth of about $200,000, a wife and children. However, greater ambitions called.

From his earlier banking apprenticeship and subsequent readings in economics, he had hatched some ideas for bringing prosperity to a war-torn, stagnant Europe. They were published in Money and Trade Considered: with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money (1705).

The book outlined a monetary system that had many of the features of systems now in widespread use in countries around the world. It called for a central bank to control the nation’s money supply so it could stimulate the economy when it was in recession or depression.

Law pitched his proposals to heads of state. Rejections piled up. Then a gambling buddy, the Duke of Orleans, was put in charge of France until a 5-year-old King became an adult. Law was duly appointed minister of finance.

In 1716, he established a bank where people could deposit their gold and silver coins for safekeeping and be given proof of receipts called banknotes. They could be used to buy goods and services or reclaim gold and silver coin deposits from the bank.

Since only a small percentage of the depositors were likely to seek redemption of their banknotes at any one time in the normal course of affairs, the bank could print unbacked banknotes to make extra loans. This would expand the money supply, allowing more businesses and consumers to buy goods, services and assets – thereby stimulating commerce.

The Duke and Law also wanted to boost the French economy by developing trade with its resource-rich colony of Louisiana (later sold to the United States in 1803). Its territory was a massive tract of land spreading north from New Orleans all the way to Montana, with the Mississippi River running down the middle.

Hence, the creation of the Mississippi Co. in 1717. It was given a monopoly on trade with Louisiana, and authority to issue shares for raising funds. The shares were heavily promoted and made purchasable in easy instalments with the help of loans from Law’s bank.

With the promise of untold riches in Louisiana and easy financing terms, demand for Mississippi Co.’s stock was insatiable. The price soared from 500 livres to 10,000 livres between April of 1719 and February of 1720 – a twentyfold gain within 10 months.

Hundreds of French citizens became millionaires (a French term that originated from this episode). Law’s stake made him the richest person in Europe, outside of royalty.

During the mania, several more issues of Mississippi shares were floated to finance operations and acquisitions. One acquisition was particularly monumental: the purchase of the government’s debt for its interest payments.

The stimulation from the bank became too much. Inflation started to take off and erode the real value of the banknotes. Citizens increasingly flocked to the bank to reclaim their gold and silver. Long queues formed and riots broke out.

To slow down inflation and halt the run on the bank, Law began to dial down loans to businesses and to investors buying shares in Mississippi Co. This was the pin that pricked the bubble.

Looking back in his Oeuvres completes (1934 ed.), Law wrote that he had some remedies to stabilize the situation but just as the economic crisis hit in 1720, a plague broke out in France and brought commerce to a standstill.

The bank started again pumping up the money supply and making more loans. But ongoing outbreaks in the virus and bottlenecks in supply chains did not allow merchants and farmers to respond quickly to the demand. Particularly damaging, Law wrote, were the clogged coastal ports through which supplies from Louisiana and other countries could not get through.

As the crisis tumbled out of control, calls arose to carry Law off to the gallows. Talk about déjà vu…. He hastily fled France, his fortune in tatters. For the next nine years, he wandered Europe, playing at gambling tables, until his death in 1729.